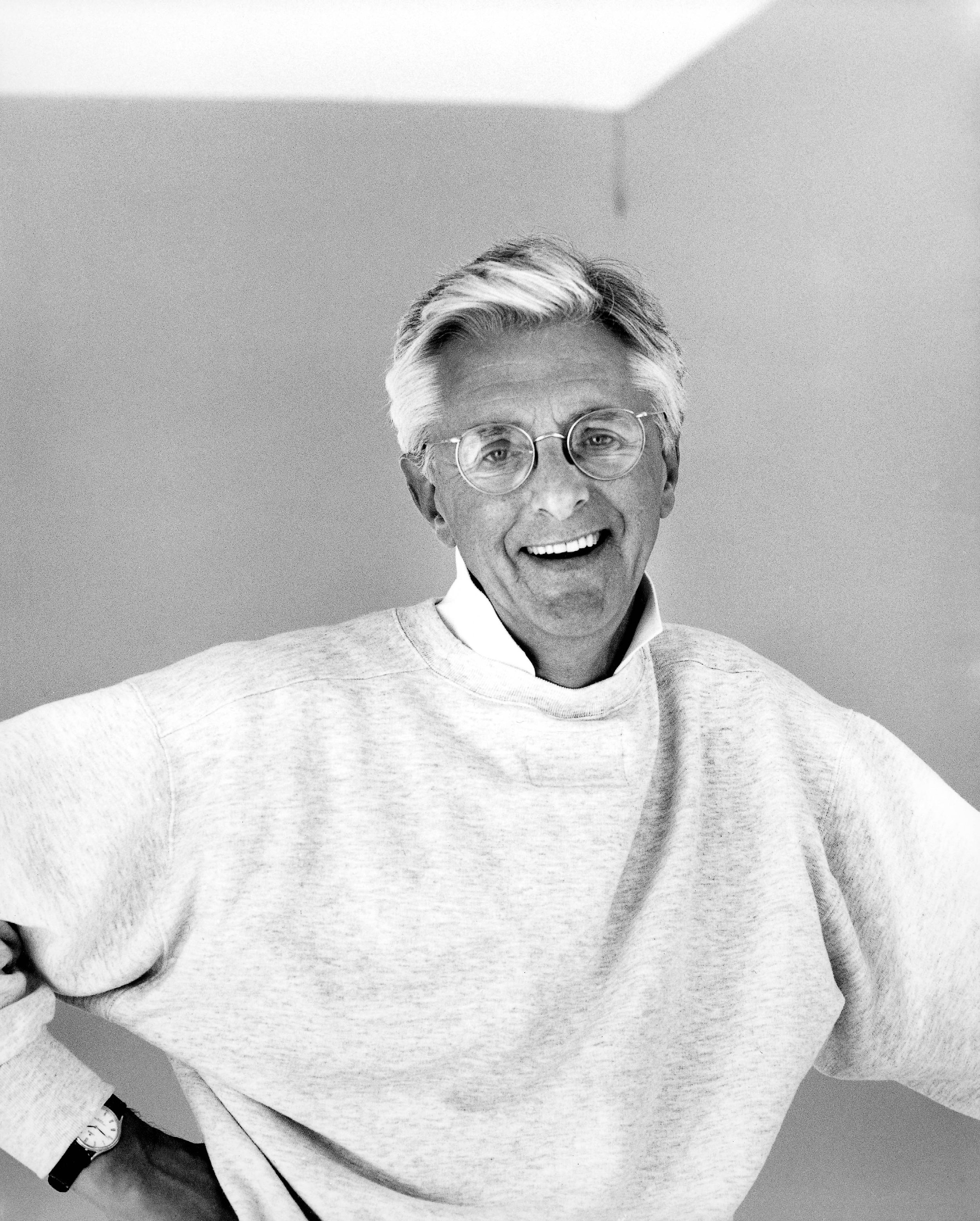

Anthony “Crix” Crickmay

(May 20, 1937 - January 8, 2020)

Anthony Crickmay, was the most eminent photographer of British dance and theatre culture of the past half-century, whose pictures of Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev in rehearsal were among the first revelations of the magnetic intensity of their partnership.

He photographed the 23-year-old Richard Gere in his career breakthrough, headlining the London premiere of the new musical Grease in 1973, an image of strutting rock’n’roll manhood that made Gere a star. Crickmay also took exquisite pictures of ballerinas in fashion shoots, and historic studies of the great actor knights Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson and others.

In his 60-year career, Crickmay became the leading visual historian of the art of late 20th-century dance in Britain, creating striking images of the rise of contemporary dance at a time when the form had no other permanent record.

Above all, he brought a young man’s camera eye onto the Royal Ballet at the point when Nureyev exploded into it, and his intimate, impressionistic way of photographing the company’s most brilliant performers exposed the art of ballet in a new light, as a vivid and present theatre experience, rather than a carefully posed frieze.

With the grainy textures of news photography, such pictures had a raw immediacy that chimed with the Royal Ballet’s rising reputation as a world centre for ballet as dramatic theatre.

Crickmay made many of his earliest images in rehearsals, trying to expose both the athletic beauty of motion and the spontaneous emotional risk of artistic interpretation. Such pictures captured a new side of the idolised Fonteyn, who in her forties revealed herself as a powerful dramatic artist in her partnership with the young Nureyev, particularly in his probing 1963 photographs of them rehearsing Frederick Ashton’s tormented Marguerite and Armand.

His books of photographs of dancers revealed something of the individual charisma and gifts of each artist, the classical poise of Anthony Dowell, the spontaneity of Lynn Seymour, the precision of Wayne Sleep’s astonishing virtuosity, or Arthur Mitchell’s elegance. They also conveyed truths about dancing as a vision of motion through time -- whether sculpting bodies like timeless marble statues, or capturing a soaring dancer in air in their exultant defiance of gravity.

Some Crickmay photographs were perfect objets d’art in themselves, microscopic studies of the muscular detail of contemporary performers’ bare feet, or an image of Darcey Bussell in her Swan Lake tutu as decorative as a Fabergé jewel.

His great friend, the modern choreographer Robert Cohan, said that a Crickmay photograph was “not just a photograph of a dance but a photograph about dance.” Yet these were also photographs about photography, since trapping instants of speed and climax were challenges to lighting and timing that many following photographers would learn from.

However, he also achieved riches and a place on thousands of teenagers’ bedroom walls with one of Athena’s most popular poster images, a moody study of young lovers in a meadow with a vintage Ford Prefect called “The Outsiders”.

Anthony John Crickmay himself started with outsider’s odds against any such illustrious career. Born on May 20 1937 in Dorking, Surrey, he was the younger child of a charming car salesman, Jack Crickmay, and the former Winifred Alice (“Peggy”) Main.

Jack Crickmay came from a renowned family of Dorchester architects and his grandfather, George Crickmay, had in 1870 employed the budding novelist Thomas Hardy as his assistant on church restorations. But there were many sons, and Jack and his older brother Stuart both went into the car business.

After the war, during which Jack served in the Royal Army Service Corps, his marriage to Peggy broke down, which put a stop to Anthony’s schooling at Belmont School, aged just 15.

Anthony and his sister, June, who was 22, went to London, in somewhat desperate straits. Both found beds in hostels, June in a ladies’ club, Anthony as the youngest in the homeless men’s hostel. The next day, packing the holes in his shoes with newspapers, he hunted for work and got a job parcelling up the orders for Wallace Heaton’s photographic suppliers in New Bond Street.

He soon progressed to the sales counter, where he met the renowned Viennese photographer Lotte Meitner-Graf, who offered him an apprenticeship at her London studio. He always credited Meitner-Graf, a specialist in velvety black and white portraits, as his chief teacher and influence.

In 1958 Crickmay set up on his own by sending an invitation to everyone he knew to take their portrait for £3, labelling it “an offer you simply cannot refuse”.

One of his satisfied clients, the pianist Ivor Newton, suggested he take photographs at Covent Garden, where in June 1961 his pictures of a rehearsal of Franco Zeffirelli’s production of the opera Cavalleria Rusticana were seen by Zeffirelli himself, who remarked, “You know, these aren’t bad.” That launched his career.

The following day Crickmay had his first encounter with dancers, photographing the Kirov Ballet in their Western debut at Covent Garden – in the absence of Nureyev who had just sensationally defected in Paris. When the Russian joined the Royal Ballet soon after, Crickmay was in prime position to take historic photographs of the thrilling young Russian and the turbulence he brought to a rather staid ballet scene.

Crickmay’s ability to communicate in photography made his pictures of the 1970s contemporary dance boom equally important. Radiating his fascination with the more stripped-down physicality of barefoot performing, Crickmay’s images could lure even dyed-in-the-wool traditionalists to acknowledge that modern dancers might be as attractive as ballet dancers. Many of his pictures, collected in a 1989 book, London Contemporary Dance Theatre: The first 21 years, have become treasured records of artists, theatre craft and works that had big impact in their time.

Seeing the visual potential in the meeting of superlative movement and superlative dresses, he had his studio customised with a sprung floor and mirrored walls, to give prima ballerinas such as Darcey Bussell and the Bolshoi Ballet’s Natalia Bessmertnova the confidence to make marvellous images for Vogue and the weekend colour supplements

In the 21st century Crickmay’s seductively colourful photographs became the visual branding for the publicity materials of the Royal Ballet, Rambert Dance and Northern Ballet, much emulated by younger photographers

In 2017 the V&A held an 80th birthday exhibition of 130 of Crickmay’s photographs. Crickmay was also an accomplished portraitist. The National Portrait Gallery holds seven of his photographic portraits, including those of The Queen and Queen Mother and the choreographers Sir Frederick Ashton and Sir Kenneth MacMillan. He was particularly proud of a groundbreaking series of pictures he took of Tony Blair and his family at 10 Downing Street for the Sunday Times.

Anthony Crickmay kept a second home in Marrakesh, where he met and fell in love with a young Moroccan, Abdou Doulaki. In 1982, Abdou sadly died; Crickmay remained in mourning for Doulaki for the rest of his life. In 1991 Crickmay set up the Abderrahim Crickmay Charitable Settlement in part to honour his life with Abdou.

Text courtesy of Ismene Brown

Header image by Everton Waugh, courtesy of Camera Press

© Eve Arnold/Magnum Photos